At the conclusion of a recent tournament stretch that tested my skills and endurance, a moment from Michael Bamerger’s new book, The Playing Lesson: A Duffer’s Year Among the Pros, came to mind. I played two tournaments in two states over seven consecutive days, finishing second in the Arizona Open, before traveling to Scottsbluff, Neb., a remote town three hours from Denver, to play in a pro-am. My longtime friend and fellow pro, Jhared Hack, helped me land a spot in the event the year before, when my bank account was low. I had finished third. The check from that event was a lifeline to the remainder of my season.

Jhared, 35, has played in PGA Tour events, won dozens of mini-tour events running away (by his count, he has 60 such wins), once shot 57 with a bogey, gained Korn Ferry Tour status a few times, and lost his game completely. He had the driver yips, to the point the widest fairways on a golf course looked like bowling alleys. I witnessed firsthand many of Jhared’s foul balls (and the helplessness that followed). In 2018, he missed 16 straight cuts on the KFT. How that stretch didn’t completely crush his spirit speaks volumes about Jhared. Those were the low times. He moved to Las Vegas, started caddying at Shadow Creek, worked hard, met the right woman, and buried the yips in the desert.

A few weeks ago while playing the final round of the Colorado Open, Jhared told me he had $214 in his bank account. He hoped a sponsor would cover the entry fee for Q school, but hope can’t write a check. Jhared barely had the money to get to the next tournament. But he put on a chipping clinic in the final round, shot 69, finished T-9 and took home $4,800. A few days later, he pocketed $2,100 at the Arizona Open with a T-13 finish.

The following week, Jhared and I battled with about 60 other pros in the Platte Valley Companies Pro-Am over 54 holes in Scottsbluff. Jhared was two strokes ahead of me and had the lead after two rounds. The morning before the final round, he revealed he had put the $5,500 entry fee for PGA Tour Q school on a credit card. (The checks from the past two tournaments probably hadn’t even hit his account yet and he’d already spent them.) If he closed out the tournament, Jhared planned to sign up for DP World Tour Q school as well. So the stakes for the day were high, and 18 holes later, I rolled in a 20-foot birdie at the last to move into solo second, one stroke behind Jhared. He had a 10-foot par putt to win outright. When it slid by, Jhared and I were headed to a playoff for the $10,000 top prize.

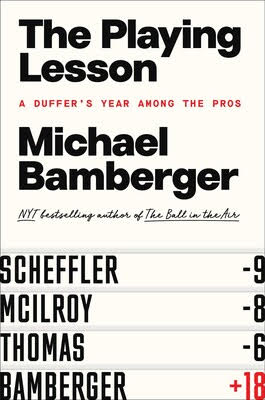

For The Playing Lesson, Bamberger spent a year traveling the country and abroad, participating in pro tournaments in various capacities and documenting his adventures. He volunteers in Palm Springs, caddies at Pebble Beach, plays in a Waste Management Open pro-am, spends time with obscure pros, explores an Epson Tour event in Florida, takes lessons from a legend in Ohio, hangs out in municipal course card rooms in Augusta, and covers the men’s and women’s U.S. Opens in his normal role as a golf scribe. There’s also a brief story about a Taiwanese LPGA player named Wei-Ling Hsu at the 2024 U.S. Women’s Open, which our playoff in Scottsbluff connects to.

In 2024, 29-year-old Wei-Ling was nearly 8,000 miles from home, had just missed an LPGA cut, and was trying to remain optimistic. Wei-Ling’s mother is Buddhist, and while caddying, she often applied Buddhist teachings to golf shots. The Middle Path is a fundamental concept to Buddhism: find a balanced approach to all of life’s situations. Wei-Ling describes how it applies to golf shots as “you don’t take too much, but you don’t take too little.” In other words, don’t be too greedy; take what the golf course gives you. A day after a missed cut, however, Wei-Ling was struggling to find peace.

“I might look like this sweet girl,” she told Bamberger. “But I could come off the course and want to punch something. I worked on that. Now I try not to go crazy. But you don’t let go of all of that.”

As she drove southbound on the Jersey Turnpike between tournaments in the Northeast, a thought crossed her mind: her game, her beliefs, her motivation, and her tenacity had led her to the LPGA tour, and to a start in the upcoming U.S. Women’s Open. She radiated with pride. In Lancaster, Pa., a week later, those thoughts came to life in every shot she played. Bamberger writes:

“Her play there was spectacular. I’m not saying that just because I am a new member of the Wei-Ling Hsu fan club, although I am. I’m saying it because she was in control of her golf ball for four straight days on a demanding golf course…I saw her play some pitches and chips, and hole some curling par putts that were mind-boggling in their excellence. She made ninety-nine thousand dollars, a huge step toward keeping her LPGA playing privileges for the following year. That week at Lancaster, she got everything out of her game that was there to get. That’s some feeling.”

We all hope to hit our best shots in every situation, but to do it when it really matters – when people are watching, or during a high-pressure situation at the end of a tournament – that’s transcendent. Consider all the rounds of golf you’ve played that really tested you, the rounds where you have to remind yourself to breathe, where your mind and your heart race, and where on-course obstacles appear fatal. Consider what it felt like when you were finished, having navigated the voices in your head and the on-course dangers successfully, when you enjoyed a post-round drink and recounted the day with friends.

There’s a deep and unspoken satisfaction in that. Wei-Ling and other competitors had just navigated a U.S. Open, and it was time to take a breath. It was time to let their hair down. As they finished, players filtered into the grillroom at Lancaster Country Club.

“It was a warm Sunday afternoon in early June, but this grillroom—above a gym, next to the driving range, across a parking lot from the main clubhouse—felt more like a ski lodge after the lifts have closed,” Bamberger writes. “Caddies and players and their family members were bopping around, bottles of beer and cocktail glasses in hand, going from table to table congratulating one another for playing, and surviving, a U.S. Open. The next tournament for those playing it, the ShopRite Classic near Atlantic City, was two hours away by car, and the hotel was on the property. You could fall out of bed and find yourself on the driving range. Two easy courses (relatively speaking) and a purse one-seventh the size of the U.S. Open purse. A holiday with prize money, really. Wei-Ling would be heading there soon enough. Mike Whan, a well-liked former commissioner of the LPGA tour and now the CEO of the USGA, was making the rounds in the grillroom, chatting up the spent players. It was intimate. Golf is meant to be intimate. A course is big, the hole is small, the clubs are odd, the terminology is strange. Golf could not possibly be for everyone. But it does promote intimacy. That is one of its great attributes. Wei-Ling was taking it all in. Every person in that room, in various ways, knew how the others felt. If that’s not intimacy, I don’t know what is.”

.jpeg)

Back in Scottsbluff, Jhared and I teed off on the opening 520-yard par-5 playoff hole. Altitude, heat, and adrenaline carried my tee shot down the fairway so far the ball refused to come down. “I’ll see you in two shots,” Jhared said with a laugh. He had a hybrid into the green; I had 126 yards left to the middle.

Many of the amateurs who played in the pro-am stuck around to watch the playoff. An army of carts followed us down the fairway; there might have been 40 carts weaving around, searching for the best vantage point. Jhared missed the green with his approach and I hit a good wedge 13 feet behind the hole. Jhared left himself some work after a long, awkward chip. I committed the cardinal sin of leaving a slick eagle putt a few rolls short. Jhared made his eight-footer for birdie like it was routine. We continued on.

Each of us birdied two of the next three playoff holes with a few dramatic shots before returning to the par-5. I split the narrow fairway again and had another wedge in. Jhared kept his drive within 30 yards of my ball this time and played a brilliant iron to 12 feet. My wedge covered the flag the entire way. “Be good,” I said. The ball surprisingly stuck where it landed on the firm green, leaving me three paces short of the hole.

Jhared won the 2006 Western Junior, and in 2007, he won the Western Amateur, beating Dustin Johnson and Rickie Fowler in match play. Many suspected Jhared’s career would look similar to Johnson and Fowler’s. In golf, you never know. Jhared has grinded through all three stages of Korn Ferry Tour Q schools three times since. He has made some big putts over the course of his career, and the 12-footer on our fifth playoff hole in Scottsbluff fell in the hole with perfect pace.

I had a 10-footer to extend the playoff. My ball had settled in an awkward location perched atop a small spine. I fully expected to make the putt. I went through my routine, hit a good putt, looked up and watched the ball slide by on the low side. I was disappointed after a long, hard-fought day, but happy for my friend. Had it not been for him, I wouldn’t have been there. We’ve made it through Q schools together, stayed in rental houses without power during tournaments, once huddled in a bathroom closet during a tornado warning at a tournament in Texas, and been there for one another through the highs and lows. All of those experiences were in the handshake that ensued on the playoff green. I was proud of him and his resilience. This was another experience to add to the list, and as he drove through the night to a qualifier for his next tournament, we texted back and forth about the day.

“That putt on the first playoff hole was lucky to go in. I hit it thin,” Jhared wrote with a laughing emoji.

You don’t need to have dueled a friend in a five-hole playoff for Q school entry fees or survived a U.S. Women’s Open to know about the intimacy golf creates. In The Playing Lesson, Bamberger weaves sentences through time with freedom, optimism and humility. There are layers underlying his words. There are layers to this game. We are bonded to those who have faced similar trials, shaped by those experiences, and love the game even more because of them.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

0 Comments